Why people hide AI usage at work?

Essay Outline

- The reasons

- Implications on other employees

- Difficulties for organizations

- Opening the closets

- Starting small, aiming big

- Ask and you shall receive

- Begin from the top

- Publicize the adoption with face and numbers

- Revamping incentive structure

- AI-tools ready hardware

- Celebrating doping in sports

- Policy framework

- De-stigmatizing AI usage

- Going local

- Adapting business goals

- Hiring for AI-readiness

- Fighting the resistance

- Managing Tech-Doom Crusaders

- Demystification sessions

- The way ahead

In 2022, when I came across DALL-E and ChatGPT for the first time, I was hooked. I spent hours and hours of my time tinkering with them. Apart from the fun, I wanted to find out their capabilities and limitations. What a feeling! Consequently, I couldn’t stop myself from sharing about it with the people I cared for. I had to share it with everyone I knew. I just couldn’t resist.

Why couldn’t I resist myself from sharing about these tools?

The answer lies in human psychology.

It is one of the most widely studied behaviour in the field of marketing. And while there are no right or wrong answers, I have a favourite answer: people purchase things or spread the word because it elevates their status in comparison to others.

Immediately our mind begins to verify this answer.

- “Sent from my iPhone” signature in emails

- “My BlackBerry Pin is xxxxx” (if you remember this, you’d also remember the glorious decline of that techno-social phenomenon)

- And the latest one was the Studio Ghibli phenomenon

If it doesn’t elevate their status, people neither purchase things nor spread the word.

So, after the rise of industry-changing AI tools in past 2 years, we would have imagined a scenario:

- Workplaces teeming with conversations about AI tools

- Teams celebrating every new win they make in outsourcing grunt work to AI tools

- People chatting about how they applied which tool to speed up their earlier process

- Organizations incorporating AI-gains in their value chain

- Hiring managers creating new frameworks for new hires to ensure they’re AI-ready

- etc…etc..

But that is not what happened.

Sure, different surveys indicate that the usage of AI tools has increased multi-fold among employees. Take the latest one by KPMG, sampling 48,000 people from 47 countries.

Click here to access the full report

58% employees use AI in their regular work. In emerging economies such as India, 72% employees are using AI compared to 49% employees in advanced economies.

The numbers are solid.

The adoption is fast and at an unprecedented scale.

But.

But.

But, the interesting thing is that not all who acknowledge AI usage at work in a survey actually acknowledge AI-usage in their work in their workplace. Saying “yes” in surveys, saying “no” when asked by a co-worker.

And that’s half-fascinating, half-confusing.

Why would people pass the opportunity of elevating their status by showing off their experiments and productivity with AI tools?

In other terms, why do they hide their AI usage at work?

The reasons

We can only guess what each individual’s reasoning might be. But when taken as a group, we humans are not that mysterious. It is little bit easier to assume a range of reasons for a group employees than an employee named Paresh. Let’s try to touch as many dimensions as possible.

The AI-stigma

Many managers frown at the mention of AI usage in their work. It may not be as direct as frowning at a team member when they bring up the news of the latest AI tools, but it might be something quite indirect:

- A subtle condescending tone while talking about AI

- It might be their doomsday postings of “copyright violations, energy consumption…AI iS BaD..bEcAuSe cLiMaTe cHaNgE..”

- It might be their attitude on AI’s reliability. There is a small echo chamber on internet that is hell-bent on finding faults with AI’s output which occasionally feeds their bias.

These attitudes seep up through the organization and what once used to be a team-limited “uncomfortable silence” turns into “stigma”, a “taboo”.

Most people do not want to engage with people harbouring irrational and unreasonable attitudes. This AI-stigma is no different. Team members read the room and they lay low. They do not share their findings and use cases about AI in their work. They become secret cyborgs.

Organic vs Inorganic

There’s a Korean channel on YouTube that publishes detailed process of how different products are made. They’re mostly from South Korean artisans and factories.

For example, I loved this one where the craftsman create beautiful Hiking Shoes by hand.

I’m sure people might pay above the market price for these shoes. After the industrial revolution, the supply of factory-made, high-quality products replaced the hand-made, moderate-quality products throughout the world.

Still there is a special kind of reverence, a spiritual ego boost in doing things with hands. Perhaps, Mahatma Gandhi appealed to this quality in people when he called on to them to boycott factory-made, English clothes.

This reverence for organic elements also permeate the modern work. For the workforce that has been in the market for last 3-4 decades, using AI tools may seem inorganic…inhuman. Feeding the cycle of shame.

Role of shame

“Shame is the fear of disconnection—it’s the fear that something we’ve done or failed to do, an ideal that we’ve not lived up to, or a goal that we’ve not accomplished makes us unworthy of connection. […] Shame derives its power from being unspeakable. That’s why it loves perfectionists—it’s so easy to keep us quiet. If we cultivate enough awareness about shame to name it and speak to it, we’ve basically cut it off at the knees. Shame hates having words wrapped around it. If we speak shame, it begins to wither. Just the way exposure to light was deadly for the gremlins, language and story bring light to shame and destroy it.” – Daring Greatly, Brene Brown

Shame researcher Brene Brown has provided some of the foundational ideas on why we feel shame and how to get over it.

When it comes to knowledge work, is it any wonder that so many people might be feeling to have failed to live up to the ideal of “hand-craft”? It stands to reason that a Creative Head would appreciate their junior’s “hand-crafted” headline copies more than the ones provided by an AI tool in 30 seconds. Even if the AI ones were far better.

Imagine the condition of someone who works in an environment where accepting AI usage in their work is a matter of shame.

And that’s how shame sets its roots. Shame gets stronger with each unspoken word. Each hidden usage.

The efficiency trap

In most organizations and society in general, people who get work done faster than others, are underappreciated and suspected of compromising quality than their slower counterparts. Even if the faster people’s quality of work was better than the slower ones. It is probably one of those psychological illusions that we humans have developed over the years of evolution: “if it is fast and cheap, it is too good to be true.”

Most AI-users are aware of this efficiency trap. They know that completing and delivering work more efficiently than their peers may draw attention and unnecessary doubts about their quality of work. The solution to this trap is age old: deliver the work in average time. Sometimes with variation in quality1.

AI and doping in sports

In competitive sports, doping is use of athletic performance-enhancing drugs by athletes. It is a way of cheating.

Failing a dop test is a matter of embarrassment and humiliation. It is a career-ending event for athletes.

Due to whichever combination of reasons, if employees feel that AI usage is frowned upon in their organizations, AI becomes the performance-enhancing drug. A drug that lets people produce better work but they can’t admit their usage. And let’s be honest, the sweetest fruits are the ones that are forbidden.

In the wise words of Acharya Rajneesh: “निषेध से आकर्षण बढ़ता है।” In context of our discussion: निषेध से उपयोग बढ़ता है।

Fear of job loss

Another reason is simple and understandable. If employees begin disclosing their AI usage in work and if AI seems to be surpassing their competency (which it will), the employer and colleagues would judge them as replaceable cog in the wheel. Combine this with the AI doom-and-gloom narratives. And you have created an existential threat.

Take a look at some headlines from this year.

Almost every headline is programming the workforce to be fearful of AI. To treat it as an enemy. When so many screens scream at you with the same message, it is difficult not to internalize it.

And that’s one of the irony of employees hiding their AI usage: they’re seeing its benefit first-hand but they’re unable to reconcile it with the messaging of the doomsday scenarios, ultimately giving in the fear.

To exaggerate their contribution value

Perhaps, this might be one of the main reasons behind people’s under-reporting of AI. If they can produce a better work with less effort and time, they stand to gain multiple things:

-

Social status and career push by the perceived high contribution from them

-

Put considerably less effort and time. This increases the money-to-actual effort ratio. They don’t get additional cash per se. But we are going in with the assumption that “most people want to disconnect the effort and outcome equation”. That’s what we call leverage.

AI acts as a lever

“Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.”

– Archimedes

In post-industrial economy, no technology other than internet has held as much leverage as the current AI technology does. Almost all knowledge workers (and many manual workers) have access to the AI lever. Interestingly, most people do not want to show off this lever. Because showing off the lever may rob them of their leverage.2

This non-disclosure or under-reporting of the actual AI-usage provides an edge in workplace competition. If someone doesn’t know what or how much of a tool you’re using, they can’t prepare an effective defence against you. (As noted in the footnote above, I don’t think that’s a good and lasting career strategy.)

“Shadow AI” usage

Shadow AI is the usage of AI tools that happen outside security oversight, increasing risks related to data exposure and violation of secure cyber practices.

As found in this survey, “57% of enterprise employees input confidential data into AI tools”.

That’s the percentage of people who knew they were dealing with confidential data AND chose to answer accordingly in the survey. The real number would be way higher than that. And what do we mean by confidential data exactly? Here’s the breakdown from the survey:

31% reported entering personal details, such as names, addresses, emails, and phone numbers.

29% disclosed project-specific information, including unreleased product details and prototypes.

21% acknowledged inputting customer-related data, including contact details, order histories, chat logs, and recorded communications.

11% admitted to entering financial information, such as revenue figures, profit margins, budgets, and forecasts.

Any wonder people would hide their AI usage? Especially when they know they might be exposing sensitive data to AI models.

Before and After comparison

By sharing the extent to which someone is using AI in their work, they expose themselves to the scrutiny of their work without AI. And most likely, their work would seem subpar when compared to the AI’s output.

Disclosing usage of AI in their work draws a solid line in their career: “Work BEFORE AI” and “Work AFTER AI”.

For most normal folks like me and you, smart usage of AI in our workflow would make our ”BEFORE AI work” look dim in comparison to our “AFTER AI work”.

It is only humane to not want to put ourselves in such a situation.

Response to “what do you bring to the table?”

In the face of existential uncertainty in their career, whether a person is gainfully employed or looking for a job, almost every interaction seems to be asking them: “what do you bring to the table?”

Hiding the AI-usage might seem like their answer to that unasked question. It gives them a justification to get retained or hired, although that would not last very long.

Implications on other employees

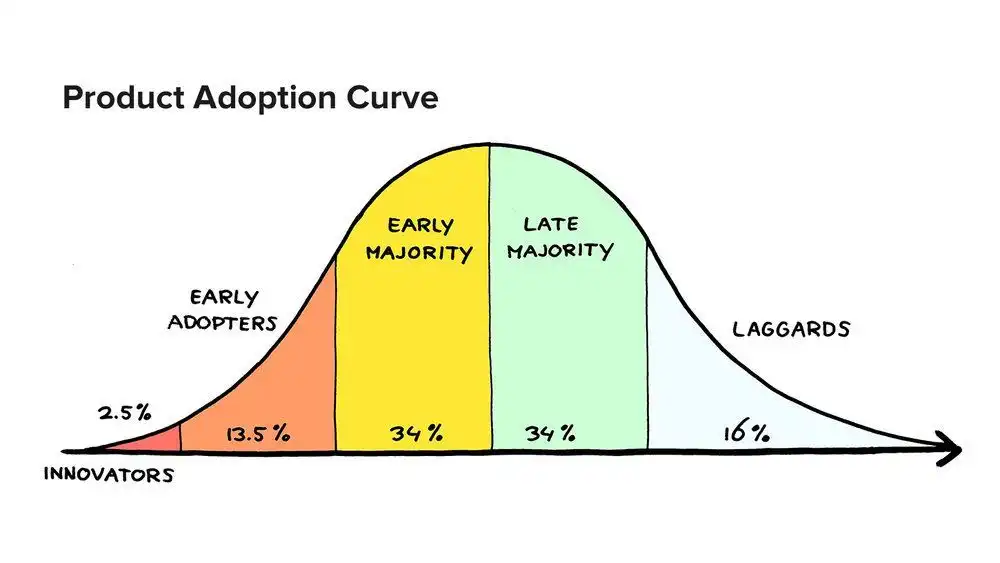

As it is with any innovation, the early adopters are always in the minority. So far in our discussion, we have talked about this minority: the employees who have been using AI in their work. They’re powerful and their impact is not localized. But it affects the majority: the employees that are ignorant to the relevance of AI to their work. These employees fall under the other category of people who are not early-adopters (the 85% of any group). We need to briefly discuss how the minority’s secret usage of AI affects the majority, and consequently the organization.

Late to the party

“What we have learned so far is that using AI well is a skill that needs to be carefully learned by… using it a lot.”

– The AI Memo, Tobias Lutke, CEO, Shopify

Most people using AI to augment their day-to-day work fall under the “early adopters” category. And most of them hide their adoption. As long as they keep it a secret, the rate of adoption to “early majority”, “late majority” and “laggards” will be extremely slow. Because it is the early adopters and early majority that spreads adoption of new ideas.

And ideas that don’t spread, die.

The act of not sharing AI usage in work, leads to a series of problems for everyone on the other side of the adoption curve.

The later the rest of the crowd sees the effects of AI in their work, the later they will tinker with it. And the later they tinker with it, the more difficult it would become for them to catch up due to these factors:

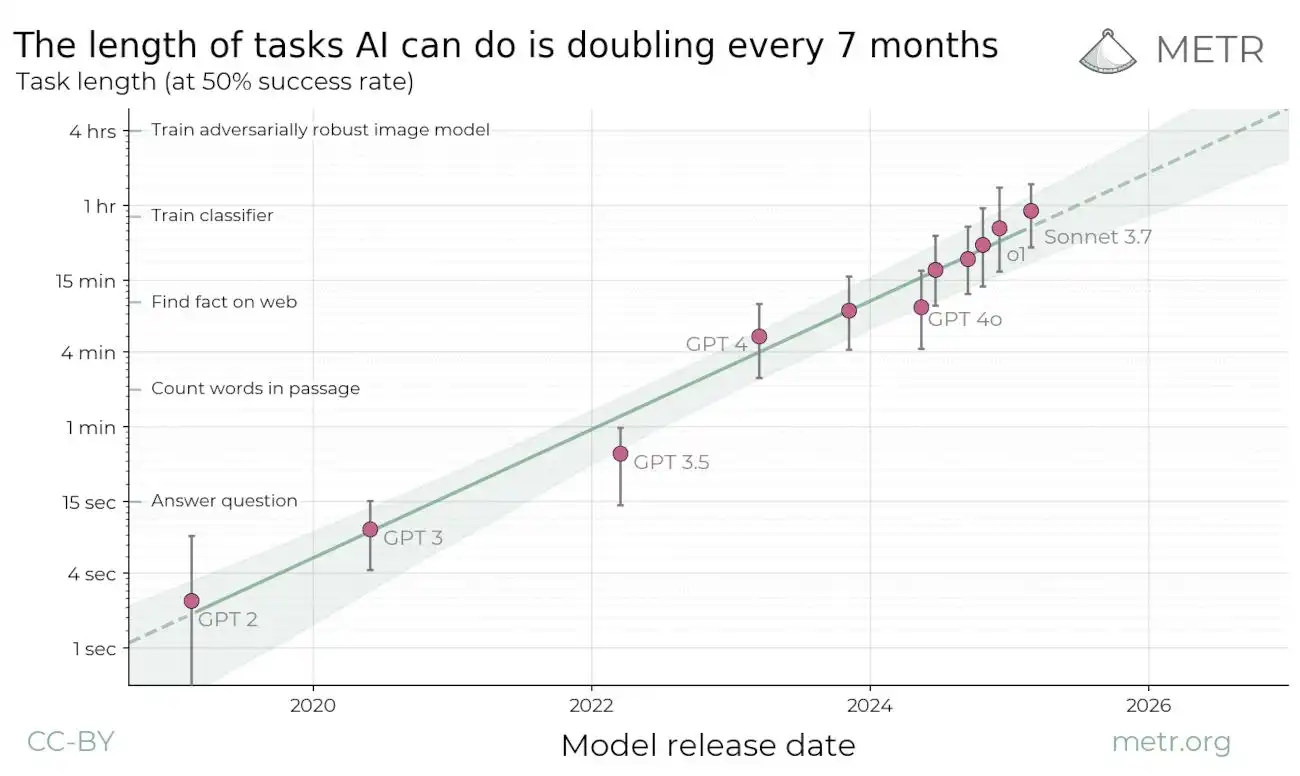

- Steep learning curve: As reported by METR (Model Evaluation and Threat Research), the AI’s ability to complete tasks at 50% success rate has been doubling every 7 months for last 6 years!3 If this trend continues–which seems likely–the late adopters will have to face a steep learning curve because of the increased complexity of AI systems.

- Futility: Having missed the early train, the late adopters may feel that catching up with their AI-ready competitors is simply futile.

- Skill-gap: Trying to tinker with a more evolved AI would make the uniniated feel that the gap between his/her skill and the AI’s skill is staggering. This would in turn engender the “futility” feelings.

- Not getting the reps: What Tobi pointed out in his memo to his people is spot-on. AI is not a genie and learning to use it requires tinkering. A lot of tinkering. The more time and practice one gets, the better. But someone who tries to adopt AI late would not hit the reps that an early adopter would have hit. In other words, they wouldn’t be able to punch in their 10,000 hours.

Parity with the stars

Every organization has a small star performer group and a big non-star performer group. If both groups begin tinkering with AI simultaneously, the initial phase may prove motivating to the non-stars because after all, they’d be able to create and solve ideas that previously were mostly monopoly of the star group.

This parity brings a sense of accomplishment. Euphoria. A quick win. It a powerful motivating factor to keep tinkering with the AI and keep improving. But hiding the degree of AI usage robs the non-star group of people to taste this parity with the stars. And eventually, costs the organization value creation.

Of course, this parity is unlikely to sustain because the tool’s usage is user-dependent. Eventually, star performers would remain top performers due to their domain knowledge, experience, and creativity. But the non-star performers would be nothing less of a 10x of their previous selves. And that is what counts.

Hopelessness

When organizations and their people create an echo chamber that banishes AI tools, majority of their people catch the late train (how late? that’s one of the deciding factors) to the world of possibilities.

The implication of being on the last lag of AI adoption may instigate the feelings of hopelessness (it is different than feelings of futility). These feelings get further reinforced when some of the risk-takers and well-connected fellows reach different heights in the organization using AI tools.4

Missing out on AI use cases

AI tools are “solutions” for which we have to find matching “problems”.

There’s no SOP, no playbook. People have to use AI in their day-to-day work and find out what works and what doesn’t work. It helps them develop intuition about what AI can do and find their eureka moment for their workflow.

This is an important experience that the other employees miss out on.

Consequently, this may perpetuate the false belief that AI tools are useful in some select domains only. “Not in my work…my work is too complicated to be done by AI”.

Feeling lost

In the middle of already strong narratives about doom-and-gloom scenarios, not knowing how the other employees are “making it” to the next rung, it is natural to feel lost. If no meaningful intervention is provided, it leads to the individual’s career stagnation and loss of interest.

Organizations might see a wave of such lost faces in the coming years.

Difficulties for organizations

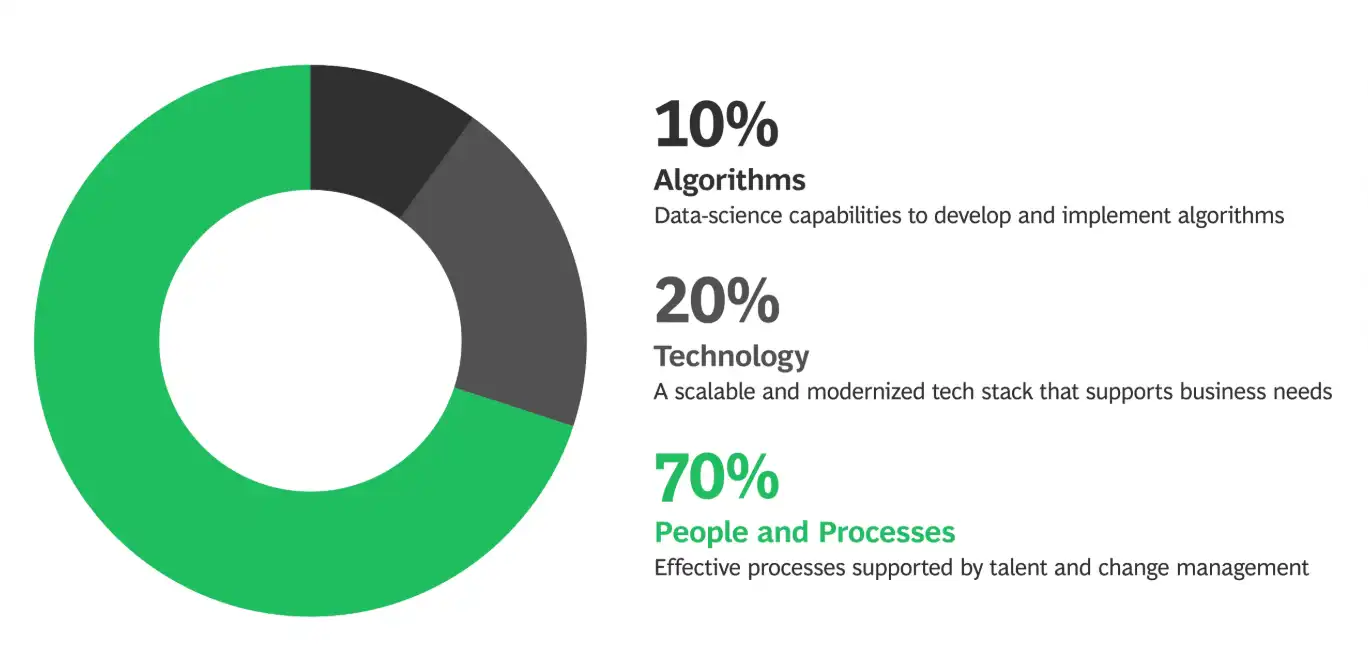

Every organization is unique and complicated. Hence, it is difficult to estimate the cost of the hidden usage of AI for any organization.

So what can we do? Instead of looking for exact dollar or hour values in cost, we can list the difficulties such organizations would face. And let each organization assess what it would cost them to overcome those difficulties.

If an organization chooses to completely ignore the increasingly AI-dependent value creation in the world, their cost would be paid in the form of lost relevance.

Measuring and rewarding

Long before the rise of AI, organizations have been struggling to measure and reward performance “fairly”. It has never been a perfect system. Now, the additional layer of AI-enhanced performance is beyond capacity for most organizations.

For example, before introduction of AI, a junior programmer could complete 10 units of tasks per week. After its adoption, he is able to complete 50 units of tasks per week. That’s a four-fold increase in his performance.

How do we measure it? And subsequently, how do we reward it?

Determining baseline performance

Naturally, after a year or two of AI-enabled workforce, it would be extremely difficult to understand what baseline performance looks like for a given task. Here, “baseline performance” is the minimal expected work output of certain quality by an individual who is relatively new to that specific work.

Since the organization would be used to seeing AI-enhanced work for a long time, it would be difficult to judge the performance of the prospective hires (even if they’re AI-ready) for similar tasks. Their performance would seem dismal when compared to their counterparts already in the business groove and equipped with AI.

Without a reasonable standard of baseline performance, it would be difficult to judge someone’s work.

Naming a fair price

Similar to the problems of measuring and rewarding, compensating people fairly would be a tough task. There are two types of compensations issues that organizations would run into:

-

The AI-adopters: These members would have been with the organization before the AI revolution. They adopted AI, contributed to the organization’s growth. In many cases, initially self-taught and self-funded AI adoption, later funded by the organization to continue the work. Since the AI adoption would increase productivity by 10-50x, reflecting in profit too, how would the organization price the AI-adopter’s additional value creation?5

-

New AI-ready hires: Before AI, pricing a role was already a difficult task. Now this task has an additional layer of gauging: the organization needs to understand not only the candidate’s raw capacity but also AI-enabled capacity.

Estimating the conversion factor

I was struck by this idea while writing a footnote for one of the former paragraphs. Understanding the importance of this idea, I feel obliged to expand it as a separate heading.

Suppose an organization is operating a coal mine and recruiting miners through contractors. It’s a manual coal mine. Each contractors are paid in the proportion to the coal mined by their miners. If the contractor brings more miners, or experience miners, it would reflect in the increased output on a daily basis.

Here, we can draw a straightforward cause and effect relation between the number of miners and the quantity of coal mined. Under ideal condition, the conversion factor of the productivity gains is almost 1. Every addition of a miner leads to → increase in coal mined, which in turn leads to → more money for the coal company, which leads to → more money for the contractor.

Now, with AI, we are not dealing with coal mines or miners. But like the coal company, organizations live on profit. Their business value leads to profit.

The tough question for organizations is to estimate how much of the additional business value gains made by the AI is actually converting to profits. This conversion factor will always be in ranges. And estimating this range is important for making long-term investments in AI at organization level.

Estimating this conversion factor is one task, another task is to get a consensus on the conversion factor. Since it is not an exact science or arithmetic, organizations would need to invest heavily in making sure that the basis of these estimates are as indisputable as possible.

How do you measure engagement?

For most knowledge workers, showing up at 9 to 5 job in the office is a mark of successful engagement. If they’re remote, answering a phone when called, being present in virtual calls and not messing up deadlines might be a mark of successful engagement.

But now when the AI-augmented employees can do the same work at the 10x-50x speed, organizations may need to change the terms of calling an engagement successful.

And what would those terms be?

- The number of successfully submitted assignments?

- The quality of successfully submitted assignments? (If yes, who would decide that?)

- A high ratio of quality/time-to-complete?

- Impact of assignments to the direct profit? (If yes, how would they determine the conversion factor?)

- The degree of innovation?

- The difficulty level of problems getting solved?

Confidentiality dilemma

Encouraging people to adopt AI may sound as easy as asking them to sign up for personal ChatGPT account and begin tinkering with it for work. But as we discussed in one of the previous sections, a majority of workforce is feeding confidential and sensitive information to AI tools. It may seem like a no-harm-no-foul practice until a major security incidence takes place.

The challenge for organizations is to define, implement and monitor different security practices for their people. And even after implementing guardrails, organizations would need to identify certain business operations that should never be exposed to AI tools.

Risk mitigation

As we discussed, training people on best practices of safe AI-usage, maintaining boundaries and monitoring their compliance are difficult tasks. After implementing them, if there is still a breach of confidential data or any similar incidence, how would the organization respond?

Every organization would need to re-assess their vulnerability and prepare mitigation plans. The points of vulnerability would be drastically different and far more in the post-AI business processes than the pre-AI ones.

Getting the top teams on-board

In most of the mature organizations, the executive team comprises of executives with a wealth of experience. Getting them to try the AI tools is ironically difficult.

There are couple of reasons behind this:

- Chasm between workers and decision-makers: After years of experience making high-level decisions and not being involved into the day-to-day, it might be difficult to draw a parallel on the applications of the AI in day-to-day operations for their workers.

- Just another bubble: Senior executives have seen all rain-and-shine and bubbles in technology domain. Thinking that AI is just another bubble is an easy trap to fall into.6

- Worker protection: Even if they are convinced of AI’s usability, with a misplaced sense of protecting their workers, the top teams may want to postpone AI-integrated work culture.

Upskilling or re-casting?

On an average, for most mature organizations, a significant portion of the workforce is older than the the rest. While old age doesn’t necessarily translate to learning-challenges but there would be instances where it becomes difficult to learn new tools and model their application in day-to-day work. This is going to be a widely spread problem in any organization.

Depending on their nature of job, experience and competency, a minority of these employees would need upskilling while the majority would need to be recast in a way that capitalizes on their strengths. They may never need to touch AI tools, but only direct the other team members.

Hence, organizations need to be prepared for a humungous organization-restructuring exercise.

AI interaction changes processes

Until now, we have been considering AI tools as just another set of tools that need to find their space in our workflow. We have assumed that the old pipeline would remain unchanged. But the reality of effective AI tool usage is two-way. We modify AI tools to fit our workflow and the AI modifies our workflow to maximize its benefits. This is an automatic process. The more we begin to integrate the AI tools in our workflow, the more we are challenged to question our processes.

Now, if you have seen organizations grow, you’d quickly recognize that this has been true for any enterprise software too. For example, if you subscribed to a CRM software for your organization, there is only so much you can customize. Ultimately, your staff needs to make changes to their processes to align with the software workflow.

But but..AI tools are different. They’re flexible. They can meet where you are.

The question is, where do you want to meet the AI tool?

And that’s the question that trips most organizations. There are no right or wrong answers here, but it helps to be creative and ambitious in this undertaking.

Hidden liabilities

As reported in the reasons earlier, “57% of enterprise employees input confidential data into AI tools.” We also discussed that the real number would be far greater than the 57%. And it was just one survey.

This trend means only one thing: organizations are unaware of the degree of their liabilities. It cannot be measured right now and so can’t be mitigated.

Organizations, whose business survives on their proprietary practices and deals with sensitive information at scale, they would need to revisit their security practices.

Unpredictable overhead

If organizations recognize the need for AI tools and begin supporting their people with organization-wide access to premium AI tools such as ChatGPT Plus, what would be their overhead? That’s a little bit predictable since it is a subscription-based model.

But things get complicated fast when organizations decide to use AI APIs in their workflow. Since API services follow usage-based pricing, the cost projection is complicated. This part is difficult but not exactly unsurmountable. Organizations need to set right expectations about the financial and technical complexity of this part from the get go.

Read more: A primer on how to navigate through AI API costs if you’re thinking to implement AI in your workflow

Opening the closets

By now, you, the reader would have realized that the task at hand is tough. Handing over AI tools subscription to your people is not going to make it. But still, you have to start somewhere.

Organizations can begin by setting up some concrete goals. One of the goal can be as simple as: encouraging people to be honest about their AI usage and inspire others.

To achieve their goals, organizations can employ combinations of different strategies. Overall, the following actions can be undertaken to implement strategies.

Starting small, aiming big

In 2022, the business world was awash with AI-integration news. Start-ups, grown-ups, everyone was announcing their version of “we’re ditching whole teams for AI tools”. None of them were as loud as Swedish fintech giant Klarna’s decision to replace their customer support staff of 700 people. To be replaced with AI. By 2025, they had to resume hiring customer support staff since the AI tools were not as effective as actual humans.

None of us knows what exactly went wrong with Klarna’s AI tools, but we can be sure of one thing: they tried to start big in over-enthusiasm.

Learning from examples such as Klarna’s failures, organizations can start small. As we discussed before, AI tools are solutions we need to search problems for. We need to understand our context and processes first. Once understood, we can identify a small, automatable task in a workflow that can be used as a pilot. And build on it slowly.

Iteration is the key here. Integrating AI in organization processes is similar to developing a good software. In this case, the organizations experience what goes wrong during the development process, the same way a software developer sees the bugs first-hand.

When organizations begin such small scale pilots, it acts as a magnet for people who are using AI in their work. They feel related and willing to contribute.

Ask and you shall receive

Requesting team members to come forward with their experiments with AI is a low-hanging fruit. It is straightforward. And one of the most effective action managers can take. It doesn’t require any drama, strategy, 10-people-meeting or a memo. Simply asking and encouraging team members to begin sharing their AI-usage in work.

Agreed, it may not guarantee a full disclosure from people, but organizations have to begin somewhere.

Begin from the top

Leading by example is a powerful strategy when it comes to AI usage in the workplace.

As we discussed earlier, while it might be difficult to get some of the executive team members on-board, they can be pursued by experiencing small bits of AI usage in their work. It has to be meaningful though. It can be as simple as providing an AI-enabled summarizer bot that summarizes key insights from one of the dashboards they’re used to look at.

The more visionaries of the lot at the top can also begin treating the non-adoption of AI among their teams as existential threat–which it is true–and that may move a needle.

Publicize the adoption with face and numbers

Shopify’s Tobi adopted AI from the outset and kept sharing his tinkering journey with the world at large. Especially with his people. Same goes for many people at top of the hierarchy.

Dharmesh Shah, the CTO of Hubspot, has been vocal about his tinkering with AI tools for a long time. He has already built an interesting AI product: agent.ai

Whether it is Tobi or Dharmesh or anybody of their stature, by publicizing their usage, these people are not only leading by example, but also they’re getting a real-world feedback. Not to mention, the kind of top talent they might be attracting towards them.

Revamping incentive structure

“Before asking for more Headcount and resources, teams must demonstrate why they cannot get what they want done using AI.”

– The AI Memo, Tobias Lutke, CEO, Shopify

The last part of the Tobi’s memo is quite interesting. He has rightly drawn a line as any business owner should. If you notice, Tobi hasn’t indicated that people are going to lose their jobs. But he has clarified that people owe some justification before asking the organization to spend additional resources.

So, how do we incentivize people to be intellectually honest in justifying their need for additional headcount?

One way might be to share a percentage of expenses saved with the people. If 10 employees are doing the work of 15 people, they need to be incentivized by money, time, and status for the savings of 5 people worth of expenses. How much to be incentivized? We’re back to estimating the conversion factor.

And if people get greedy, not expanding their team for additional incentives, it would reflect in their deteriorated performance.

AI-tools ready hardware

Most companies tightly regulate their company-issued devices to keep them secure. But sometimes, it makes it difficult to experiment with AI tools, which may require new combination of security parameters. There are solutions available in the market that doesn’t compromise security and data while allowing tinkering with AI.

Organizations need to invest in understanding their requirements and getting the solutions that suit their needs.

Celebrating doping in sports

The history of sports is filled with controversies of doping athletes and their humilation. For an elite athlete, being found guilty of doping is a career-ending event. In such a culture of preserving human potential, integrity and hardwork, what if someone celebrates doping? What if they encourage doping in competition?

That’s what the Enhanced Games events are going to do. They’re scheduled to inaugurate in 2026 where the participating athletes would have trained on performance-enhancing drugs. As controversial as it may seem to be, the founder Aron D’Souza has taken a bold step and tapped a whole different market.

In the world of business, organizations need to rethink the way their people work. They need to have their own Enhanced Games version of teams. Celebrating AI-enabled performers and acknowledging their contribution.

Policy framework

Adopting an organization-wide AI policy and providing controlled infrastructure is one of the most effective ways organizations can protect themselves against unsafe AI usage that would lead to unlimited liabilities.

Ideally, the framework should be tailored for each organization’s specific needs, however, one can start by using templates such as this one published by PwC. [Attach the document]

De-stigmatizing AI usage

Stigmatic topics remain stigmatized for not seeing the light of day. One of the ways to de-stigmatize them is to talk about them. Sounds boring but organizations can get creative without spending much effort.

There are different ways to create a space for such type of discussions:

- Organizing weekly/monthly discussion groups

- Beginning a newsletter, highlighting organization-wide updates, including AI-usage stories

- Publicizing case-studies about what worked and what didn’t in your organization

Going local

It is tempting for many organizations to rope in external parties to encourage and educate their people on AI usage.

There are at least two possibilities when people from outside are brought in:

One of the most common ones is the increase in internal resistance. If not handled well, outside hires, whether they are consultants or conference speakers, get pushback from the people. There might be several reasons behind such internal resistance: such as lack of shared business or cultural context, lack of time for developing rapport between outsiders and insiders, etc. This may do more harm than good.

Another not-so-common but not-so-impossible one is when there is total submission, almost a reverence for the outsiders. People may even feel grateful for the guidance and support they receive from the outside hires. This is equally problematic. Because it gives rise to three problems:

- It sends a message to the employees that the organization has little-to-no innovation capacity or risk-taking attitude, and hence completely dependent on outsiders.

- It may seed the idea that AI is too difficult to be handled without outside help.

- It sends a strong signal of discouragement to the early adopters within the organization. Because if not consulted, they feel marginalized and devalued.

That’s why, taking help from internal talent is a good long-term solution. Identifying people who make AI-aided impact and inviting them to act as champions within their teams has a better ROI than any other options.

So, shouldn’t organizations hire outsiders in their AI-adoption, ever?

Not exactly.

The initial steps should be local. Once the internal champions are set and the dialogue has begun, adding external parties would only enrich everyone’s experience.

Adapting business goals

After a few months of using AI tools in different workflows, it is likely that the organization would have hit a new expectation milestone. For example, if one of the workflows includes writing SEO-friendly meta-descriptions for client websites, what used to take a week for 100 webpages, might be taking less than 2 hours.

This new expectation milestone of 2 hours should be included everywhere:

- Project timeline projection

- Performance management

- Pricing

Without formalizing and acknowledging these gains, organizations may suffer from amnesia about AI tools’ contribution.

Hiring for AI-readiness

In addition to retaining and retraining people, organizations have to look for new hires that are AI-ready for a job role. The fresh blood provides a much-needed hope and peer-training within the organization.

As discussed earlier, hiring for AI-ready people requires organizations to be clear on what exact core skill they would like to see in the prospective hire. Understanding the nature of job and setting up a baseline expectation for the new hires would help the recruitment process.

For example, if looking for e-commerce store cataloguing expert, the baseline expectation should be clear that the cataloguing expert should be able to generate meta-tags and technical copies for each product using AI tools. Not only that, they should be able to understand whether the AI-generated copy matches their client’s positioning.

This example baseline provides much better idea to the recruiters and the prospective hires than simply asking them whether they know how to use ChatGPT.

Fighting the resistance

As we discussed about AI’s impact on processes, smart organizations would quickly identify where they need to adjust their processes to match AI.

This may mean breaking from established processes or habits. Some adjustments would be necessary to reap the benefits from AI-integration.

One of the key adjustments is getting concerned people on-board. Software systems do not have any sense of preference, it is the people who do not appreciate change. Undertaking a large-scale exercise to cultivate trust and ownership in making this change happen would be necessary.

Managing Tech-Doom Crusaders

There’s a growing faction of small but loud-mouthed group of people who are on their next crusade to ban AI tools. Their reasons may vary but the underlying tone is always the same. Their message invokes a combination of these emotions: fear, guilt, hopelessness and self-loathing.

For example:

“AI is going to take over, it is going to replace us. People are already struggling to keep afloat in this economy. To top it, the amount of energy a single prompt uses is insane! It is only going to accelerate the cLiMaTe cHaNgE. We have a moral obligation to question it and save millions of people from the looming societal collapse.”

The content and tone of their sentiment may vary but the emotions they evoke remain the same.

Organizations need to identify such Tech-Doom Crusaders early on and “manage” them. If left unchecked, the organizations would pay the ultimate cost.

Demystification sessions

AI is mysterious. Calling it “AI” makes it even more mysterious and it feels alive. If we call them LLM (Large Language Model), it decreases their shine and also, LLM is an uncomfortable tongue-twister. (Try shouting LLM thrice.) Plus, using the term AI in your product increases its perceived value by several fold.

Read more: The AI domain name sales are breaking records

In such a situation, most companies developing AI or selling AI products have an incentive to keep things as much technical and mysterious as possible.

Organizations that struggle with AI adoption (i.e. almost all organizations) in their workplace have an opportunity to arrange knowledge sessions on demystification of AI. This is one of the few lowest hanging fruits organizations have. Demystification assuages fears and makes some room for reflection.

Read more: What is ChatGPT doing and why it works

The way ahead

There is nothing noble in being superior to your fellow men. True nobility lies in being superior to your former self.

– Ernest Hemingway

Depending on your job role, goals, and temperament, your ways of doing things may differ from the way of other people’s doing things. Still, we can employ a simple heuristic to track if we are progressing forward: asking ourselves “are we inching towards the goal set by ourselves?” Speed doesn’t matter as much as progress.

Here’s a list of resources to help everyone get started on their AI-readiness journey:

| Article | Author | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Using AI Right Now: A Quick Guide | Ethan Mollick | Ethan is a proponent of using paid version of products such as ChatGPT. He is right in the sense that the premium models are mind-blowing in their abilities to solve complicated problems. BUT if committing $20 is too much for you at the moment, continue tinkering with free models. Just begin. |

| Reshaping the tree: rebuilding organizations for AI | Ethan Mollick | Business owners and people in management position would find some helpful perspectives in this article. |

| AI Hallucinations on the Decline | Jakob Nielsen | I have been using different AI tools since their debut and Jakob’s analysis is accurate. When AI-pessimists say that AI output is flawed and unreliable, I know they haven’t tried the tools. |

| Power to the people: How LLMs flip the script on technology diffusion | Andrej Karpathy | I like Andrej’s analysis of how AI is empowering people and organizations. Organizations are catching up and that diffusion would take some time. |

| Stop Game Denial | Hanzi Freinacht | This article is not exactly about AI adoption. But I can’t stop thinking about how organizations and people falling in the trap of “game denial” when it comes to AI. |

| Project Vend: Can Claude run a small shop? (And why does that matter?) | Anthropic | In this fascinating experiment, Anthropic shared how their AI model Claude handled their office vending machine operation. This article will provide ideas about how AI is going to permeate in different aspects of our lives. But more than that, it will spark your imagination. |

| Integrating AI into Your Daily Work: A Practical Guide | it360inc | I found this quick and no-fluff guide quite useful for anyone looking to get ideas on AI use cases. |

| The Leader’s Guide to Transforming with AI | Boston Consulting Group | This article provides specific ideas for different management roles: sales, operations, human resource, finance, technology, risk management, and marketing. |

FOOTNOTES:

-

I can’t stop myself from thinking about one of a senior employees I worked with 10 years back. The work included creating and checking educational curriculum. On daily basis, I have seen her redoing the same work twice just to seem busy and not over-deliver. Once she suggested that I do the same to increase the value of my work. I had to politely decline her suggestion. Mind well, this was before the age of AI. ↩

-

I’m not suggesting disclosing the exact AI levers in workplace. It is possible that people might have different way of navigating through their careers. They might have different goals than what organization might have. And that is completely fine. If using AI as a secret lever/weapon is a strategic choice, then I respect that individual’s choice. Having said that, I don’t think this strategy will take them to places. It is myopic at the best. ↩

-

Summary: We propose measuring AI performance in terms of the length of tasks AI agents can complete. We show that this metric has been consistently exponentially increasing over the past 6 years, with a doubling time of around 7 months. Extrapolating this trend predicts that, in under a decade, we will see AI agents that can independently complete a large fraction of software tasks that currently take humans days or weeks. ↩

-

It is not entirely guaranteed that catching an early AI train is the sole factor behind someone’s career success. Because most times, the reality is complicated. Sometimes, early adopters are the only authority figures companies can bet on for trying out practical usage of tools. So, what seems to be a well-designed career progression from outside, might be a combination of preparation and opportunity. ↩

-

This piece of argument assumes that the value creation aided by AI is indeed translated to profits. We will probably never be able to attribute how much of the additional value created using AI translated to profits. What would be the conversion factor? Factor of 0.3, 0.5, 0.8? Your guess is as good as mine. ↩

-

If we take AI developer companies at their every word, then of course, we are setting ourselves for disappointment. Since they have an incentive to exaggerate the capabilities of their products, it is obvious that they would overstate them. But we don’t need to look up to the future. What we have at the moment is already remarkable and anyone calling it a bubble does not have your best interest at heart. Having said that, what I wouldn’t prefer is: go all-in and splurge money in the stock market rooting for some AI companies. Because again, what’s the conversion factor for organizations adopting AI? If it is making money for the organizations that use these AI tools at a very high conversion factor, then I missed the opportunity. But that we will never know. ↩

Receive new articles in your inbox

Can't see the newsletter form? Click here